Originally written in August of 2018.

When I tell people that I want to learn Japanese so that I can speak with my relatives and connect with my ancestry the reaction I often get is “wow you’re a good person for caring about family.” But I don’t feel deserving of such a compliment. From my perspective I’m not pursuing Japanese for them, I’m pursuing it for myself. To me, I have the luxury of having still-living relatives in another country; unlike most of my friends I have a rare opportunity to connect with my ancestry. It’s something that I can do that is authentic or at least it’s a path that I was born into and could not have sequestered in any other way. I’m not good or bad, just lucky.

My identity in Canada has always been Japanese through the lens of a Canadian. Canadian doesn’t mean being white, but what has distinguished me ethnically from my peers has been my Japanese heritage. I embody all the manners and motions of any Canadian, but there’s also a part of me that wanted to be unique from my peers (perhaps so I stand out and receive attention). When I was a kid my Asian identity was a conduit to being special, at least to compared to my friends. I foolishly had a narrative in my head that could be summarized as: “I’m not normal like everyone else. I have this Japanese side that makes me different. Let me show you why I’m unique so that you’ll like me.” Obviously, I did not recognize that Canada is already a place full of people from different heritages and I am no more special than the next person.

I remember the first girl I liked (we’re talking grade 3 or 4 probably) liked anime and was really talented at drawing. I thought to myself “well I have access to tons of Japanese manga, I even have some how-to drawing books.” I spent a good chunk of time practising anime eyes to impress her.

When I’m in Japan I actually have the opposite experience: all of a sudden no one knows I’m Japanese and I immediately stick out as a foreigner. Instead of wanting to stand out, all I want to do is blend in. But the way I dress and the way I walk is a dead give away. I’m just not as discreet as everyone else on the train. I don’t blend into the background like the people around me do. This transition into ‘being a foreigner’ is a story I’ve heard often from friends with mixed Japanese/Asian heritage.

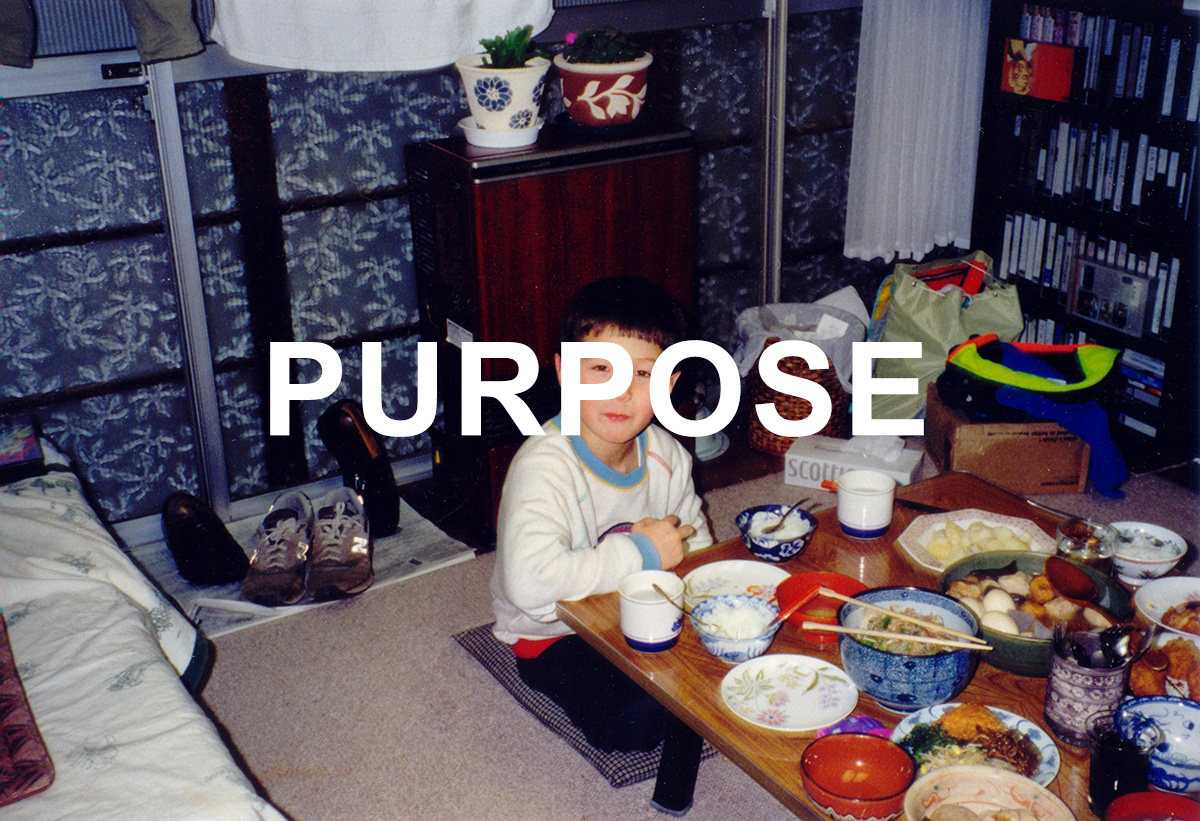

I’ve always had a Canadian identity, but my Japanese one has never felt complete. I can only speak for my experience, but try and imagine having an entire half of your family that you can’t speak to. On New Year’s Day we’d phone my Obaachan in Japan (my grandma) and say “happy new years” (あけましておめでとう) in Japanese and then immediately give the phone back to my mom (yes, we were also very shy) for fear that my grandma might ask something and we wouldn’t understand. For the majority of my life that has been the interaction with the Japanese side of my family. We’d participate when in Japan, but my parents would always be around to interpret (thank you mom and dad). This gap also meant my siblings and I were always being taken care of and looked after. Unintentionally my siblings and I were imposing a sort of responsibility onto my parents and relatives to make sure that we were never confused or lost. It meant we were by default in a position of being babysitted without a great way of returning the generosity. I’ve always wanted to close that gap so that I am not by default a burden.

So here goes nothing.

Nathan / August of 2018.

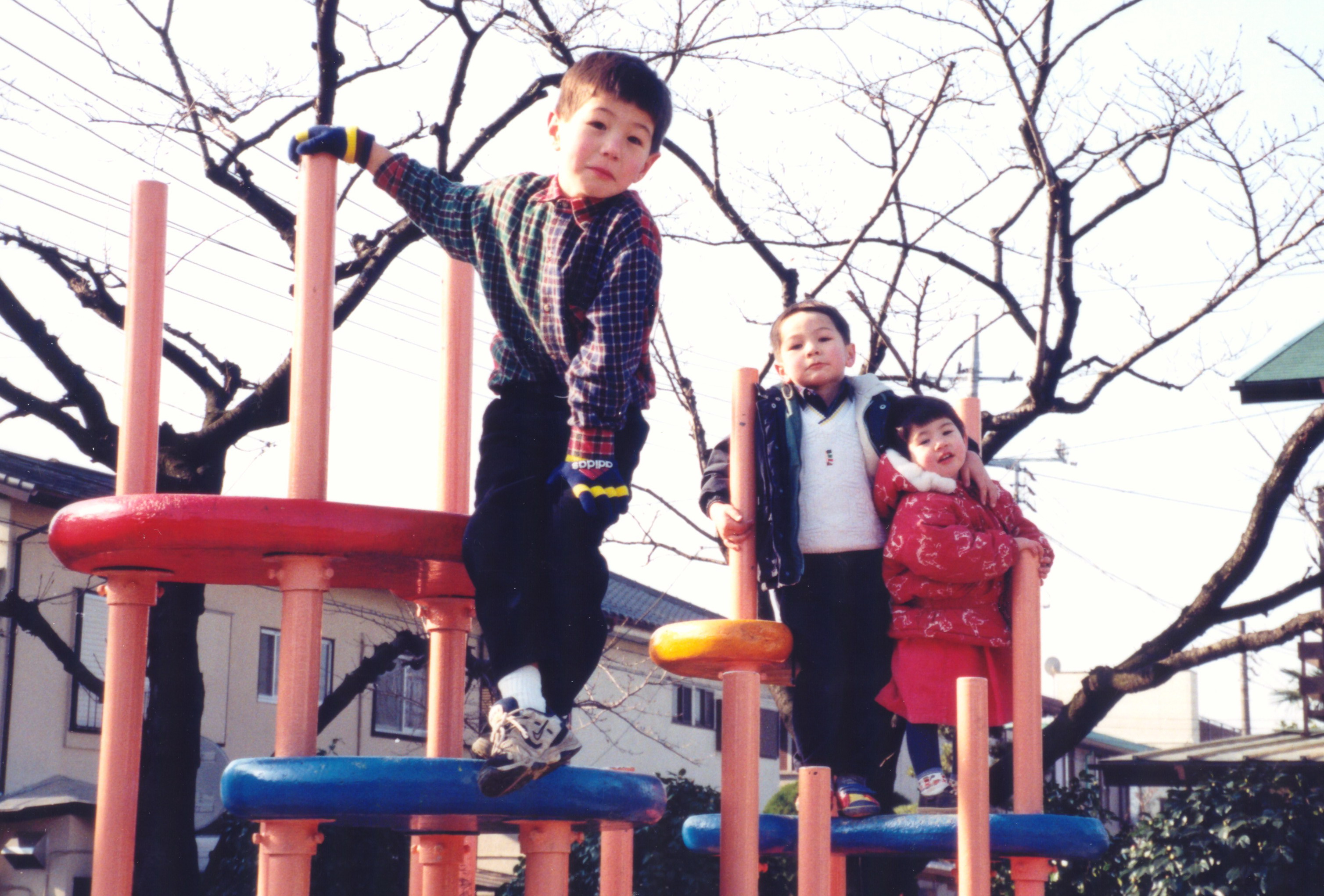

Here are a few more photos that I couldn’t find a place for: